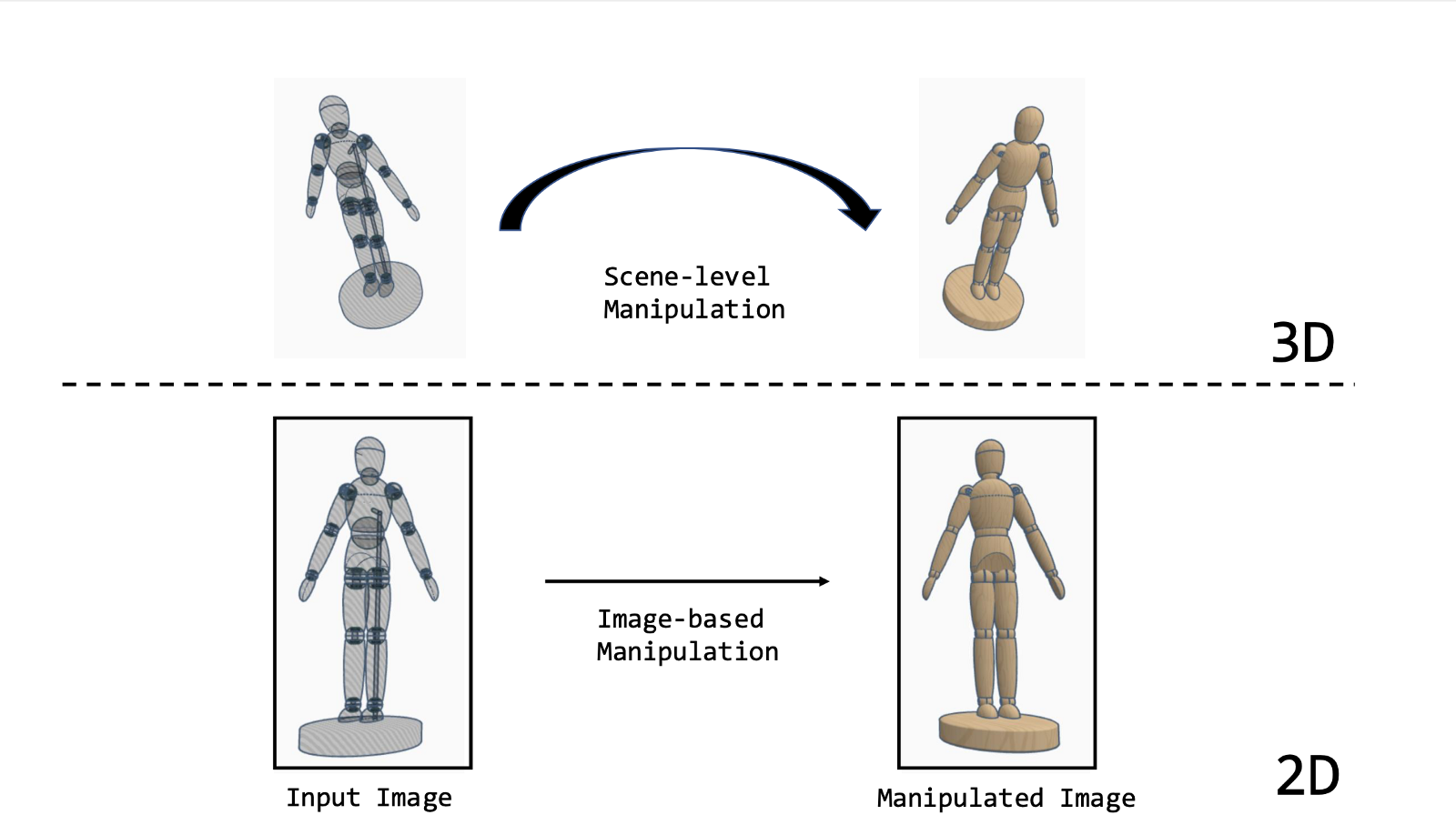

Fig. 1: Image-based scene manipulations edit 2D views of a scene to change the appearance of objects. Unlike scene-level manipulations, they do not infer the 3D information.

Fig. 1: Image-based scene manipulations edit 2D views of a scene to change the appearance of objects. Unlike scene-level manipulations, they do not infer the 3D information.

Scene manipulations, such as material editing, filtering, relighting, or geometry deformation, can be done on scene-level with traditional computer graphics techniques or on image-level with modern techniques.

In traditional computer graphics, a scene representation of an object involves explicit information of properties such as geometry, lighting, motion, camera, appearance, and semantics. Therefore, scene-level manipulation often involves the estimation of such properties for altering purposes. After the estimation of these properties from single or multiple views, desired manipulations are added on scene-level, and the resulting scene is re-rendered into a 2D view. These techniques are highly complex as the scene property estimation from 2D views is, in general, an ill-posed problem. Furthermore, adding on scene-level manipulation and re-rendering makes these approaches less desirable. Image-based scene manipulations, on the other hand, directly work with 2D views without requiring explicit information of scene properties. Hence, they avoid such complexities.

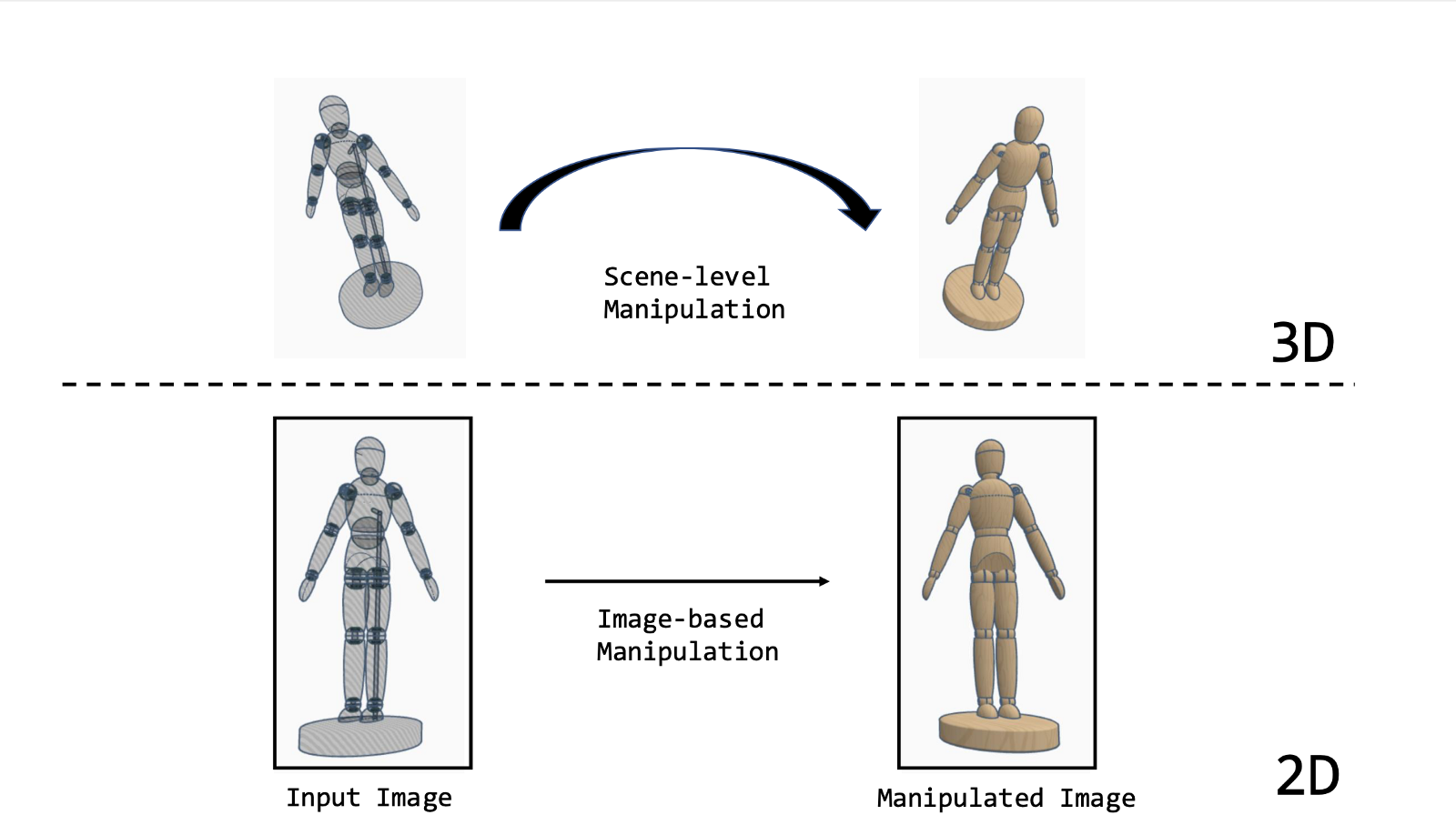

Image-based scene manipulations edit 2D views (images) to alter object properties such as shape, kind, gloss, smoothness, pigmentation, or weathering. At one end of the editing spectrum, photographers and 3D artists alter these properties manually. The upside of such approaches is that they have full control over the image. However, it is a laborious task that requires advanced skills. To ease this task, Boyadzhiev et al. 2015 describe a set of 2D image operators that are easy and straightforward to modify the appearance of materials. At the other extreme, the manipulation is fully automated with the help of machine learning (ML) techniques. In Yan et al. 2016, multilayer perceptrons are trained to learn photo adjustment effects, such as watercolor or foreground pop-out effect. However, ML algorithms can perform poorly while learning from scratch the intricate edits along with global transformations. Therefore, Shi et al. 2020 combine the advantages of both sides, professionally designed and ML techniques, and propose a state-of-the-art method to automatically convert photographs of material samples into procedural material models by estimating the parameters of node graphs designed by artists.

Fig. 2: Editing material properties, such as gloss, shade, or kind, on image-level can manipulate the appearance of materials in a scene.

In traditional photography, photographers spend a considerable amount of time designing the surface appearance of photographed objects with the help of physical techniques. In portrait photography, they adjust the lighting of their studio and apply makeup to control the appearance of face details, such as skin wrinkles or blemishes. Product photographers use dulling spray to fade the effect of specular surfaces, and in food photography, glycerine sprays can be used to show the food fresher or tastier.

In digital photography, photographers can add such adjustments to photos after the photo-shooting, using software tools rather than physical techniques. They are more advantageous in terms of timing and control over tool parameters. Nevertheless, material editing is a laborious task that requires considerable effort and expertise.

More recently, works have focused on simplifying and speeding up this editing pipeline of professional photographers with traditional or ML techniques to address novice users. For instance, Boyadzhiev et al. 2015 work with a single ordinary photograph and alter the appearance of surfaces by using predefined 2D image operations, while Shi et al. 2020 learn the parameters of the editing pipeline to obtain a procedural material model from a single photograph of material samples. Both approaches utilize artist-created techniques and integrate them into their methods.

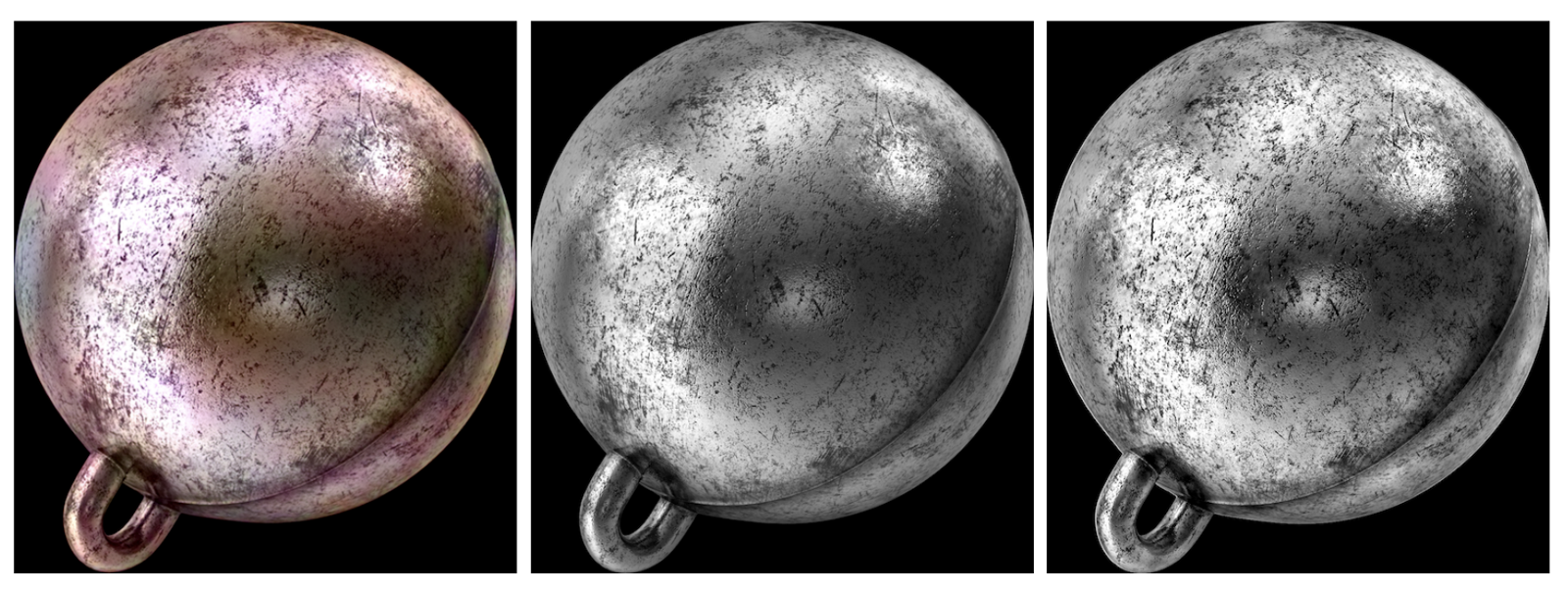

Fig. 3: Portrait relighting is a special kind of image relighting, changing the lighting properties, such as brightness and direction of light sources, on portrait photos [Debevec et al. 2000].

Lighting affects the way we perceive photographs. In traditional photography, professional photographers care a great deal about the lighting in their studio. They apply various types of traditional lighting set-ups, which create different light patterns on the appearance of their subject. The direction of light determined by the type and position of light sources shapes light patterns, such as split, loop, or butterfly, and directly affects the shadows on the appearance. As in material editing, scene relighting is a tedious task, requiring advanced skills and special equipment, such as flashes, reflectors, and diffusers.

Photographs can also be relit after the photo-shooting with some software tools. As an example, Adobe Photoshop offers the Lighting Effects filter, allowing users to choose the type of lighting source and adjust their brightness and direction. However, these tools can be highly complex, involving inverse rendering and re-rendering. In recent work, Sun et al. 2019 and Zhou et al. 2019 consider the relighting problem on image-level and train a neural network model to learn a mapping between images. However, they do not consider integrating professionally-created techniques in their algorithms.

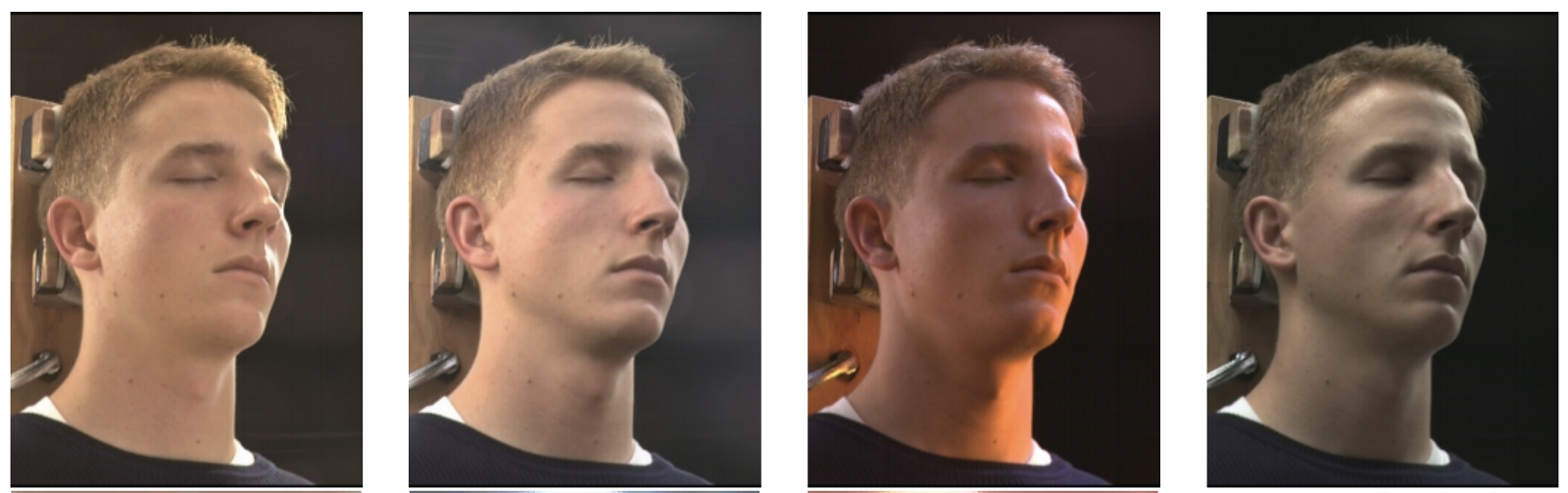

Fig. 2: Novel view synthesis from a sparse set of input images as an example of geometry editing [Mildenhall et al. 2020]

In traditional computer graphics, in which 3D information of a scene is known, the scene geometry can be represented with parametric curves and surfaces, polygonal meshes, implicit surfaces, or point set surfaces. Hence, geometry can be edited on scene-level with known 3D representations. There already exist software tools, such as 3D sculpting, CAD/CAM, or procedural, to model and edit the geometry. Some well-known techniques that are being used in traditional computer graphics to edit geometry are interactive and sketch-based interfaces, deformations, cutting and fracturing, smoothing and filtering, and compression and simplification.

Image-based scene manipulations, on the other hand, edit the geometry directly from input images. In novel view synthesis, whose purpose is to generate novel views of an object, Chen and Williams 1993, reconstruct arbitrary viewpoints, given dense optical flow between two input images. They use geometry information implicitly in their method. Also, Mildenhall et al. 2020 achieve state-of-the-art results by synthesizing novel views from multiple images with the help of ML techniques. Furthermore, Yu et al. 2021 can achieve plausible results with a single or a few input images. Nevertheless, artist-created techniques are not considered in their algorithms.